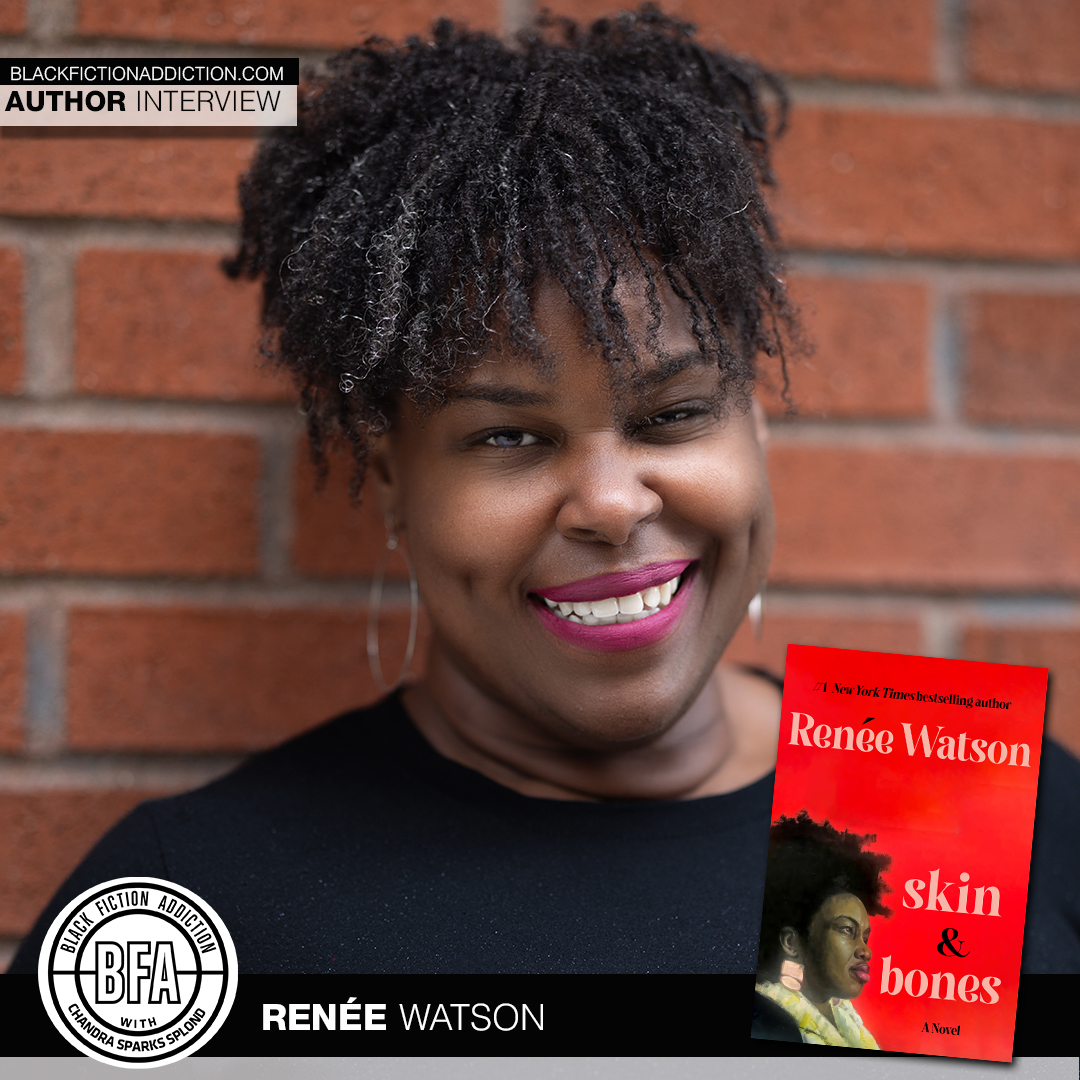

Author Renée Watson is spreading her literary wings with the publication of her first adult novel. She recently discussed skin & bones.

You’ve been a superstar in the YA world for years now, winning a Newbery Honor and a Coretta Scott King Book Award along with many other awards and accolades. What made you want to tackle an adult-themed novel?

I have been in conversation with young readers about family and friendship, beauty and self-love, and faith and activism through my fiction and poetry for just over a decade. I wanted to expand that conversation with the mommas and daddies, aunties and uncles, mentors and caregivers who love and nurture those young people.

I also felt ready to give myself an artistic challenge and finish what I started many years ago. The women in skin and bones were at first characters in a one-act play I wrote, long before I was ever published. All these years later, that story stayed with me, and over time, as I’ve grown as a storyteller and also as a woman who has experienced love and loss, it felt like it was time to take that play and develop it. It’s been something that’s been simmering on the back burner for a while.

You grew up in Portland, like your protagonist Lena Baker. In what ways do you identify with Lena and how are you different?

Though my story is not Lena’s story, I certainly drew from very real feelings and experiences of what it was like growing up as a Black girl in the Pacific Northwest. I relate to Lena feeling both invisible and visible at the same time. Because of my dark skin, hair texture, and size, I stood out, especially during my middle school years, attending a predominately White school. Even though I stood out, I was often overlooked, marginalized, and silenced. I also relate to Lena’s pride as she uncovers the rich Black history of Oregon and like her, I am still learning and finding out the story of Black Americans in the Pacific Northwest.

But this is fiction, and I am not telling my story. The thing I love about writing fiction is that I find myself relating to the emotions my characters feel while having the power to create and solve obstacles that I have never been in. Lena is an only child, and I am the youngest of five. Lena is a single parent, and I don’t have children, and while I grew up attending church, my father was not a pastor. I write from an emotional truth, but the particulars of my main characters are far from mine.

In the novel, you write about the Black experience in the Pacific Northwest and the little-known history of racism and violence in Portland and the Pacific Northwest in general. Can you share more about your research and what you were most surprised to learn about your hometown?

I believe that everything that’s ever happened to a person shapes who they are and who they will become, and I believe that applies to places, too. Every city has a story. I wanted the city of Portland to be more than a setting, but a character with a backstory. To understand Portland and all that’s happening in our present time, I think it’s important to look back and see how the city got here.

I grew up with very little knowledge of the history of Black folks in Portland, but I felt the racial tension in the city. I knew there was something different about the parks on my side of town versus the White side of town, and I lived through the gentrification of Northeast Portland, even though that word wasn’t outright used at the time. When I was a child, skinhead violence was prevalent throughout Portland. Folks seemed so shocked that this was happening in such a progressive city. There was little conversation and connection made to the rise of the Ku Klux Klan in Oregon during the 1920’s. I didn’t learn this history until I was well into adulthood. The research I did at the Oregon Historical Society and my interviews of Black elders who shared oral histories gave facts to the feelings I felt my whole childhood.

Finding out the story of how Black folks were mistreated in Portland, contributed to Portland, and thrived in Portland, confirmed that not only were there deep racial tensions in Portland’s history, but there were also Black and White Portlanders who tenaciously fought for equity and were committed to creating safe spaces and thriving communities for everyone. To understand Lena’s passion and sense of worth, insecurities, and dreams, the reader needs to know the city she was born and raised in and how that city has impacted her.

You discuss self-love, body image and the perception of beauty in your novel—do you feel the beauty, health, and wellness industries can be traps for communities of color or women in general?

Yes. I think even well-intentioned companies with mission statements focusing on diversity still miss the mark at times. Especially when it comes to body diversity. We’ve come a long way (still there’s a ways to go) regarding the celebration and acceptance of a variety of skin tones and hair textures, but still, the default for beauty seems to be thin and able-bodied. skin & bones is asking, what is beauty and what is the cost of the pursuit of beauty?

You write beautifully about mothers and daughters, female friendship, and an empowering community of women. Why was this so important for you to include in your novel?

I am who I am because of the women in my life—the women who raised me and the women who walk alongside me as sisters and friends. I can’t write about community, love, or healing without writing about the bonds between women.

You’ve noted that love has become an overused, oversimplified word. But true love is rare and there is nothing easy about it. What do you want to tell people about the concepts of love and legacy?

I don’t know that I have something to tell people about love and legacy, but I do want to ask questions about love and legacy. I hope we all interrogate our relationships, that we take inventory, and ask ourselves, are we doing the hard work of love? Are we being patient and kind, forgiving and generous? Are we critiquing and challenging, offering both rebuke and restoration? How are we nurturing and growing love? What are the things that have been passed down to us that we need to keep, what do we need to let go of?

Do you consider yourself a poet first or a novelist, and how does writing poetry influence your novels?

First and foremost, I consider myself a storyteller. Sometimes those stories come to me as poems, sometimes as novels. When I’m writing poetry, I tend to read a lot of fiction. It helps me think about story arc and characterization. Poetry has taught me to be concise, to get to the heart of the matter quickly. Just because I am writing a novel and have a lot of space, I don’t want any word wasted. In my fiction, I am very mindful of sentence structure in the same way poets are intentional about line breaks. I want to evoke certain moods throughout the story, so I pay attention to how long a sentence is, how short it is. I think a lot about the white space on the page.

Throughout skin & bones, there are poems woven in seamlessly. Can you tell us more about your writing process and the book structure?

I wanted the pages of skin & bones to be a physical representation of Lena trying to fit into spaces not made for her. There is a squeezing in, a compactness to her life that I wanted the reader to see physically on the page.

I also wanted the book to be a collage of all the things on Lena’s mind and how she processes and expresses them. She’s a librarian at heart—a lover of words. I think of her mind holding definitions, poems, narratives, history, scripture. It’s how she remembers and relates to her world. Lena is holding so much and when I sat down to write her story, writing in vignettes felt right to me. I think the story might feel heavier if it was written in traditional prose with long chapters. I wanted to move the story along, give the feeling of snapshots, fragments of memory, many thoughts coming all at once, different threads coming together to complete her full story. I enjoyed experimenting and letting the story take shape in this way.

What do you hope readers will take away from reading skin & bones?

One of the greatest compliments a reader can give me is that when they close a book I’ve written, they want to discuss it, want to debate, want to know more, that they have questions, that they want to share their own stories. I hope skin & bones continues the conversation about who society makes space for. For every reader who identifies with Lena, I hope they feel seen and validated. I hope the characters push us to rethink how we define beauty, and ultimately, I hope skin & bones brings to mind the legacy that has been left for us, the legacy we are leaving.

To learn more about #1 New York Times bestselling author Renée Watson, visit her website.

Use the Black Fiction Addiction affiliate link to purchase your copy of skin & bones.